Introduction

In the early 1470s, music started to be printed using a printing press. Music printing had a major effect on how music spread for not only did a printed piece of music reach a larger audience than any manuscript ever could, it did it far more cheaply as well. Also during this century, a tradition of famous makers began for many instruments. These makers were masters of their craft. An example is Neuschel for his trumpets.

Towards the end of the fifteenth century, polyphonic sacred music (as exemplified in the masses of Johannes Ockeghem and Jacob Obrecht) had once again become more complex, in a manner that can perhaps be seen as correlating to the increased exploration of detail in painting at the time. Ockeghem, particularly, was fond of canon, both contrapuntal and mensural. He composed a mass, Missa prolationum, in which all the parts are derived canonically from one musical line.

In the early sixteenth century, there is a trend towards simplification, as can be seen to some degree in the work of Josquin des Prez and his contemporaries in the Franco-Flemish School, then later in that of Palestrina, who was partially reacting to the strictures of the Council of Trent, which discouraged excessively complex polyphony as inhibiting understanding the text. Early sixteenth-century Franco-Flemings moved away from the complex systems of canonic and other mensural play of Ockeghem’s generation, tending toward points of imitation and duet or trio sections within an overall texture that grew to five and six voices. They also began, even before the Tridentine reforms, to insert ever-lengthening passages of homophony, to underline important text or points of articulation.

Composers of the High Renaissance (1470–1530)

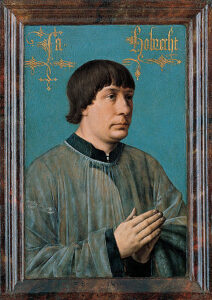

Heinrich Isaac (ca. 1450 – 26 March 1517) was a Renaissance composer of south Netherlandish origin. He wrote masses, motets, songs (in French, German and Italian), and instrumental music. A significant contemporary of Josquin des Prez, Isaac influenced the development of music in Germany. Isaac was one of the most prolific composers of the time, producing an extraordinarily diverse output, including almost all the forms and styles current at the time; only Lassus, at the end of the 16th century, had a wider overall range. His best known work may be the song “Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen“, of which he made at least two versions. It is possible, however, that the melody itself is not by Isaac, and only the setting is original. The same melody was later used as the theme for the Lutheran hymn “O Welt, ich muss dich lassen“, which was the basis of works by Johann Sebastian Bach, including his St Matthew Passion and Johannes Brahms.

Of his settings of the ordinary of the mass, 36 survive; others are believed to have been lost. Numerous individual movements of masses survive as well. But it is composition of music for the Proper of the Mass – the portion of the liturgy which changed on different days, unlike the ordinary, which remained constant – which gave him his greatest fame. The huge cycle of motets which he wrote for the mass Proper, the Choralis Constantinus, and which he left incomplete at his death, would have supplied music for 100 separate days of the year.

Isaac is held in high regard for his Choralis Constantinus. It is a huge anthology of over 450 chant-based polyphonic motets for the Proper of the Mass. It had its origins in a commission that Isaac received from the Cathedral in Konstanz, Germany in April 1508 to set many of the Propers unique to the local liturgy. Isaac was in Konstanz because Maximilian had called a meeting of the Reichstag (German Parliament of nobles) there and Isaac was on hand to provide music for the Imperial court chapel choir. After the deaths of both Maximilian and Isaac, Ludwig Senfl, who had been Isaac’s pupil as a member of the Imperial court choir, gathered all the Isaac settings of the Proper and placed them into liturgical order for the church year. But the anthology was not published until 1555, after Senfl’s death, by which time the reforms of the Council of Trent had made many of the texts obsolete. The motets remain some of the finest examples of chant-based Renaissance polyphony in existence.

Isaac composed a 6-voice motet Angeli Archangeli for the Feast of All Saint’s Day, honoring angels, archangels, and all other saints. Another famous motet by Isaac is Optime pastor (Optime divino), written for the accession to the papacy of Medici pope Leo X. This motet compares the Pope to a shepherd capable of soothing all of his flock and binding them together.

The influence of Isaac was especially pronounced in Germany, due to the connection he maintained with the Habsburg court. He was the first significant master of the Franco-Flemish polyphonic style who both lived in German-speaking areas, and whose music was widely distributed there. It was through him that the polyphonic style of the Netherlands became widely accepted in Germany, making possible the further development of contrapuntal music there.

1. Motet: Optime Divion date munere pastor ovili à 6 v.

2. Lied: O Welt, ich muß dich lassen

3. Virgo prudentissima: Prima pars

Josquin Lebloitte dit des Prez (c. 1450–1455 – 27 August 1521) was a composer of High Renaissance music, who is variously described as French or Franco-Flemish. Considered one of the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he was a central figure of the Franco-Flemish School and had a profound influence on the music of 16th-century Europe. Building on the work of his predecessors Guillaume Du Fay and Johannes Ockeghem, he developed a complex style of expressive—and often imitative—movement between independent voices (polyphony) which informs much of his work. He further emphasized the relationship between text and music, and departed from the early Renaissance tendency towards lengthy melismatic lines on a single syllable, preferring to use shorter, repeated motifs between voices. Josquin was a singer, and his compositions are mainly vocal. They include masses, motets and secular chansons. Influential both during and after his lifetime, Josquin has been described as the first Western composer to retain posthumous fame. His music was widely performed and imitated in 16th-century Europe. Josquin was a professional singer throughout his life, and his compositions are almost exclusively vocal. He wrote in primarily three genres: the mass, motet, and chanson (with French text).

4. Fortuna desperata: Agnus Dei

5. Missa l’homme armé sexti toni: V. Agnus Dei

6. Missa Mater Patris, NJE 10.1: IV. Sanctus

7. Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae: VII. Inviolata, integra, et casta es Maria

8. Inviolata, integra et casta es

Jacob Obrecht (1457/8 – late July 1505) was a Flemish composer of masses, motets and songs. He was the most famous composer of masses in Europe of the late 15th century and was only eclipsed after his death by Josquin des Prez. Combining modern and archaic elements, Obrecht’s style is multi-dimensional. Perhaps more than those of the mature Josquin, the masses of Obrecht display a profound debt to the music of Johannes Ockeghem in the wide-arching melodies and long musical phrases that typify the latter’s music. Obrecht’s style is an example of the contrapuntal extravagance of the late 15th century. He often used a cantus firmus technique for his masses: sometimes he divided his source material up into short phrases; at other times he used retrograde versions of complete melodies or melodic fragments. He once even extracted the component notes and ordered them by note value, long to short, constructing new melodic material from the reordered sequences of notes. Clearly to Obrecht there could not be too much variety, particularly during the musically exploratory period of his early twenties. He began to break free from conformity to formes fixes, especially in his chansons. Of the formes fixes, the rondeau retained its popularity longest. However, he much preferred composing Masses, where he found greater freedom. Furthermore, his motets reveal a wide variety of moods and techniques.

Jacob Obrecht (1457/8 – late July 1505) was a Flemish composer of masses, motets and songs. He was the most famous composer of masses in Europe of the late 15th century and was only eclipsed after his death by Josquin des Prez. Combining modern and archaic elements, Obrecht’s style is multi-dimensional. Perhaps more than those of the mature Josquin, the masses of Obrecht display a profound debt to the music of Johannes Ockeghem in the wide-arching melodies and long musical phrases that typify the latter’s music. Obrecht’s style is an example of the contrapuntal extravagance of the late 15th century. He often used a cantus firmus technique for his masses: sometimes he divided his source material up into short phrases; at other times he used retrograde versions of complete melodies or melodic fragments. He once even extracted the component notes and ordered them by note value, long to short, constructing new melodic material from the reordered sequences of notes. Clearly to Obrecht there could not be too much variety, particularly during the musically exploratory period of his early twenties. He began to break free from conformity to formes fixes, especially in his chansons. Of the formes fixes, the rondeau retained its popularity longest. However, he much preferred composing Masses, where he found greater freedom. Furthermore, his motets reveal a wide variety of moods and techniques.

Despite working at the same period, Obrecht and Ockeghem (Obrecht’s senior by some 30 years) differ significantly in musical style. Obrecht does not share Ockeghem’s fanciful treatment of the cantus firmus but chooses to quote it verbatim. Whereas the phrases in Ockeghem’s music are ambiguously defined, those of Obrecht’s music can easily be distinguished, though both composers favor wide-arching melodic structure. Furthermore, Obrecht splices the cantus firmus melody with the intent of audibly reorganizing the motives; Ockeghem, on the other hand, does this far less.

Obrecht’s procedures contrast sharply with the works of the next generation, who favored an increasing simplicity of approach (prefigured by some works of his contemporary Josquin). Although he was renowned in his time, Obrecht appears to have had little influence on subsequent composers; most probably, he simply went out of fashion along with the other contrapuntal masters of his generation.

9. Missa Pfauenschwanz: Et resurrexit

Antoine Brumel (c. 1460 – 1512 or 1513) was one of the first renowned French members of the Franco-Flemish school of the Renaissance, and, after Josquin des Prez, was one of the most influential composers of his generation. Brumel was at the center of the changes that were taking place in European music around 1500, in which the previous style of highly differentiated voice parts, composed one after another, was giving way to smoothly flowing, equal parts, composed simultaneously. These changes can be seen in his music, with some of his earlier work conforming to the older style, and his later compositions showing the polyphonic fluidity which became the stylistic norm of the Josquin generation. Brumel is best known for his masses, the most famous of which is the twelve-voice Missa Et ecce terræ motus. Techniques of composition varied throughout his life: he sometimes used the cantus firmus technique, already archaic by the end of the 15th century, and also the paraphrase technique, in which the source material appears elaborated, and in other voices than the tenor, often in imitation. He used paired imitation, like Josquin, but often in a freer manner than the more famous composer. A relatively unusual technique he used in an untitled mass was to use different source material for each of the sections (mass titles are taken from the pre-existing composition used as their basis: usually a plainchant, motet or chanson: hence the mass is without title). Brumel wrote a Missa l’homme armé, as did so many other composers of the Renaissance: appropriately, he set it as a cantus firmus mass, with the popular song in long notes in the tenor, to make it easier to hear. All of his masses, with the exception of the highly unusual twelve-voice Missa Et ecce terræ motus, are for four voices.

10. Missa “Et ecce terrai motus” Kyrie Eleison

11. Missa “Et ecce terrai motus” Christe Eleison